Building a Climate VIII¶

Precipitation

This lecture logically follows the lecture on atmospheric stability and introduces precipitation formation.

Information¶

Topics |

|---|

|

Atmospheric Water¶

Measuring the Amount of Water¶

For people outside atmospheric or hydrological sciences, the different ways to measure water in the atmosphere can be confusing, so we will start this lecture with some terminology:

Partial pressure of water vapour - the contribution of \(H_2O\) molecules to the pressure of air.

Saturation vapour pressure - the maximum possible pressure air can have before water condenses. This is a function of temperature.

Specific humidity - the ratio of water vapour mass to air mass. It is a mixing ratio.

Relative Humidity - the ratio of partial pressure of water vapour to saturation vapour pressure. This is arguably one of the most useful measure for water content in the air, since the ratio tells you how close you are to condensation.

Dewpoint (Temperature) - the temperature at which water vapour condenses.

Clausius-Clapeyron Ratio¶

The Clausius-Clapeyron Relationship describes the slope of tangents to the curve separating the two phases on a pressure-temperature diagram. It is therefore a way to characterise the phase transition between two phases. We can write it was:

where:

\(P\) - pressure

\(T\) - temperature

\(L\) - specific latent heat (the amount of energy required in form of heat (Q) to completely effect a phase change of a unit of mass)

\(v\) - specific volume (the volume to mass ratio for specific substance)

\(s\) - specific entropy (the entropy [“energy of substance no longer available to perform work”] per unit mass)

Clausius-Clapeyron Equation - Approximation for Low Temperature¶

For low temperature (well below the critical point) and condition in which the specific volume of the gas phase (\(v_g\) ) greatly exceeds specific volume of the condensed phase (\(v_c\) ), we can write: \(\Delta v \approx v_g\) . (The temperature at which vapour and liquid can coexist is referred to as the critical point)

If we change the ideal gas law (\(P · V = n · \bar{R} · T\) ) to make it “specific”, we get:

We can thus write:

From this and the ratio of the previous section, we can derive the Clausius-Clapeyron equation for low temperatures and pressure:

This is useful, because it lets you calculate saturation vapour pressure as a function of temperature and without information about volume.

Saturation Vapour Pressure¶

Saturation vapour pressure (\(P_s\) in this section’s equations) is a function of temperature (\(t\) in this section’s equations) and there are several (semi-empirical) approximations for it.

The Tetens equation (Tetens, 1930):

The Magnus Formula (Alduchov and Eskridge, 1996) using °C is the most commonly used equation for it:

where:

a = 17.625

b = 233.04

c = 610.94

More recent forms, e.g. Huang (2018):

Many more …

Note that this is a property of water and air plays no role in it.

Dew Point Temperature¶

For calculating dew point temperature, let us first consider the computation of relative humidity (RH) at a specific temperature:

and recall our equation for saturation pressure:

From those, we can derive our equation for dewpoint temperature:

A simplified approximation of it is possible with the equation below:

Precipitation Formation¶

Terminology¶

Let us first dive into some more terminology we will need to talk about rain formation.

Latent heat of condensation - the heat taken or released when changing the phase of water.

Cloud droplet - ca. 10 microns droplets.

Raindrops - ca. 1 mm drops.

Supercooled liquid water - liquid water below freezing point. We often find liquid water in the atmosphere that is -20°C and unable to turn into ice, because it needs a trigger to start the freezing process.

Riming - supercooled liquid meets an object and starts freezing process.

Reaching Saturation¶

There are different ways in which air can reach saturation. Roughly, they can be categorised into 3 ways:

1. Adding moisture to air:

Examples of this include steam fog. This phenomenon can be observed when cold air is above relatively warm water. The water evaporates and moisture is added to cool air, which then condensates immediately. This can happen over different bodies of water, including rivers and the sea. In the latter case, the same is often referred to as sea smoke.

Steam fog over a river (in national park ca. 100km east of Vientiane, Laos). [photo: cc-by Gerhard Mutz]¶

Other examples of adding moisture to relatively cold air include breathing out in cold weather, condensation trails, water vapour from cooling towers of power plants and more.

2. Removing heat from air:

Radiation fog over Vientiane (Laos). [photo: cc-by Gerhard Mutz]¶

Examples of this include radiation fog. Heat is radiating from the surface at night (esp. on cloudless nights when infrared radiation can easily espace). This cools bottom air until it reaches saturation. Fog forms at the surface first and then thickens as cooling continues.

Valley fog is a special type of radiation fog. As for regular radiation fog, heat is radiated from the surface during (clear-sky) nights, cooling the air just above the surface. In hilly terrain, the less buoyant cold air can then sink into valleys, much like water flowing down a hill. The fog therefore preferentially forms in the valleys of cool air. This pooling also means that valley fog can persist over longer times than over even ground.

Another example of removing heat to reach saturation is advection fog. In this case, the surface started out cold. Warmer winds then move in moisture, the warm incoming air loses heat by conduction and saturation vapour pressure drops. This can happen, for example, when warm air from land moves over a colder ocean. In a sense, it is the opposite of sea smoke.

3. Adiabatic expansion of air:

In the atmospheric sciences, this is arguably the most important way to reach saturation and condensation as it leads to cloud formation. As an air parcel (containing water vapour) rises, it cools adiabatically, which lowers saturation pressure and leads to condensation. Next, we will examine different categories of clouds and their properties.

Clouds¶

Cloud categorisation is more systematic than it may appear at first. We will have a look at a few common types. Pay attention to the recurring compounds in cloud names.

A single “puffy” cumulus cloud. [photo: cc-by Gerhard Mutz]¶

Cumulus clouds (from latin for “pile”) are characterised by a puffy appearance and greater thickness. Simple cumulus clouds are typically found in the lower troposphere. Altocumulus clouds, on the other hand, are found in the mid-troposphere. (Alto can be translated as “mid”). They sometimes form rippled patterns, which is created from rising (leading to condensation) and sinking (preventing condensation) air masses. A general rule of thumb is that subsidence prevents clouds (and thus condensation and precipitation) from forming. The ripple pattern lines up in the wind direction. Cirrocumulus clouds are typically found in the upper troposphere. (Cirro translates as “ringlet” and refers to high altitude clouds of ice crystals and supercooled droplets quickly turning to ice).

Cumulonimbus clouds, ca. 100km northeast of Vientiane (Laos). [photo: cc-by Gerhard Mutz]¶

Cumulonimbus clouds “pile up” even more than simple cumulus clouds and can reach tropopause, where they start spreading laterally underneath the stable stratosphere. They consist of droplets in its lower parts and ice crystals in upper parts. They are associated with atmospheric instability, heavy rainfall, thunderstorms and cold fronts.

Stratus clouds over Thiersheim (Bavaria, Germany). [photo: cc-by Gerhard Mutz]¶

Stratus clouds (translating from the latin “strato-” meaning “layer”) are low-level clouds forming blanket-like covers. Altostratus refer to mid-level stratus type clouds, and Cirrostratus clouds are high-level stratiform clouds consisting of ice crystals. They tend o be brigther than other status clouds and create a milky shimmer in the sky.

Stratocumulus clouds, ca. 100km northeast of Vientiane (Laos). [photo: cc-by Gerhard Mutz]¶

Stratocumulus or cumulostratus are a dark “puffy” clouds cover. They can have a similar appearance to altocumulus clouds and can also create ripple patterns. However, the individual clouds/compontents are larger in stratocumulus clouds.

Nimbostratus clouds, like cumulunimbus, are amorphous, multi-layer clouds that are dark and very uniform in appearance and associated with wide-spread continuous precipitation without thunder.

Orographic clouds are produced by air being forced/advected over mountains. As air is lifted, it expands, cools, reaches saturation and water starts to condense. As air decends on the lee side of mountains, the process is reversed: Air condenses and warms adiabatically and excess water evaporates, resulting in warm, dry air. If air lost moisture to precipitation on its way, it warms to higher temperatures on the lee side than it was on the other side at the same altitude. The resulting dry, warm down-slope wind is referred to as föhn or foehn.

Note

Have you picked up on the general naming scheme for clouds? See if you can apply this to clouds you see in the coming weeks and put it in context of what you learned about adiabatic expansion.

Formation Mechanisms¶

Rain forms either by coalescence, i.e. the merging of drop(let)s into larger drops, or by the Wegener - Gergeron - Findeisen process. The former is important in the lower latitudes, while the latter is more important in the higher latitudes.

Water droplets that formed by condensation on a window surface begin to merge into larger drops through coalescence and then sink. [photo: cc-by Gerhard Mutz]¶

The Wegener - Bergeron - Findeisen process can be summarised by the following steps:

Supercooled water droplets in the atmosphere find a freezing nucleus (e.g. dust particles) and riming starts. The ice formed by riming can serve as a nucleus to more supercooled water droplets and it draws them in. As more droplets are drawn in and freeze, the surrounding humidity decreases, resulting in surrounding droplets evaporating/shrinking. Eventually, the ice begins to fall as a snowflake, which can pick up more droplets on its way through riming.

As snow begins to fall through warmer layers in the lower troposphere, it begins to melt and turns into rain. Rain formed by this process is therefore often referred to as cold rain, which is the most common type of train in extratropical latitudes.

Precipitation Types¶

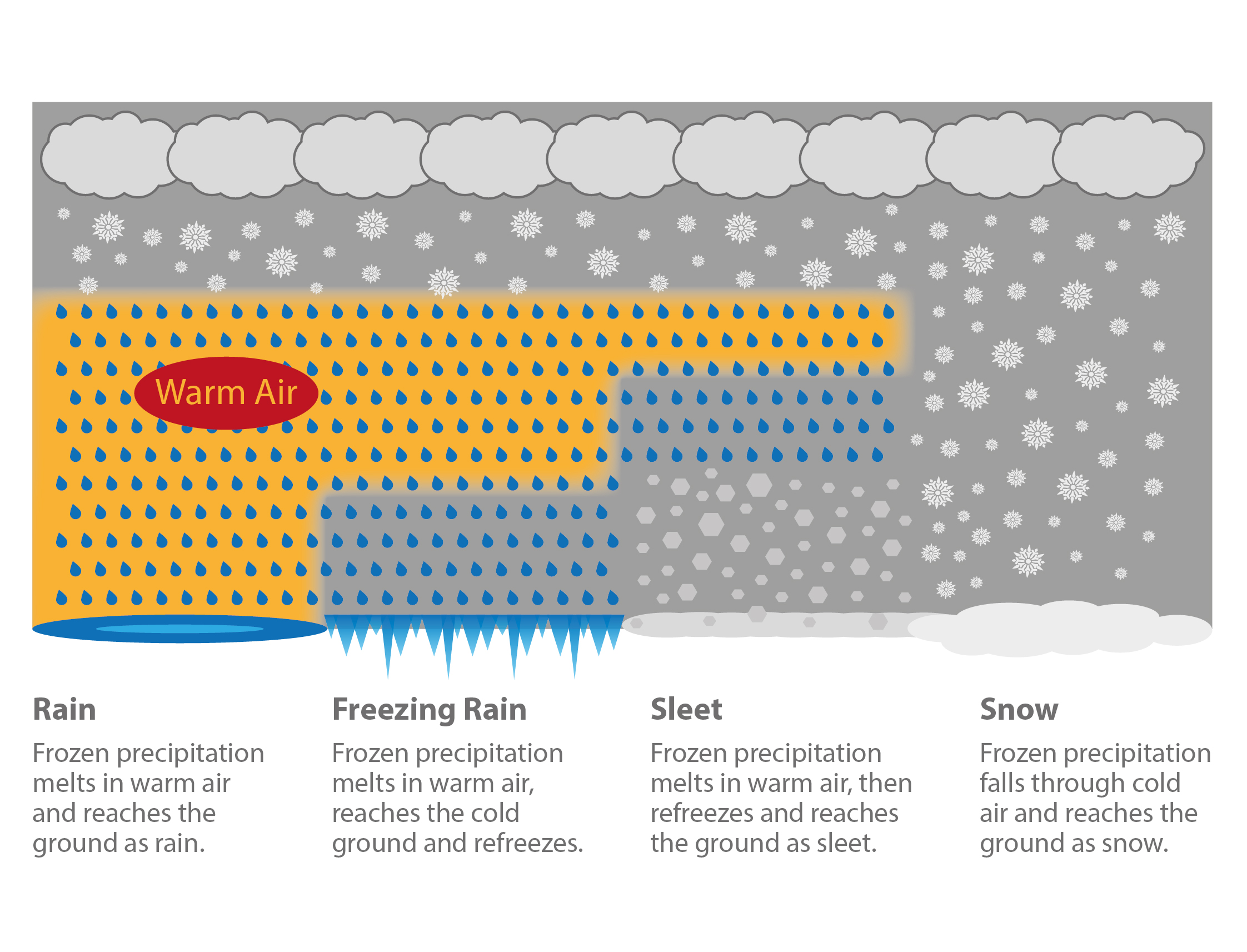

To a large degree, the atmosphere’s thermal layering determines the precipitation type. If the top of clouds are above 0°C, warm rain is formed by coalescence. If the top of the cloud is below 0°C and enough of the atmosphere below is above 0°C, we observe the ice phase process at the top and melting at the bottom. This results in cold rain. If the entire cloud is below 0°, the ice phase process is observed at the top and there is no melting at the bottom, resulting in snow.

Different types of (extratropical) precipitation caused by different vertical temperature layering in the atmosphere. [image: cc-by Lisa Rauschenbach]¶